Edition 1 – January/February 2021

Welcome to our inaugural edition of “The Arc”, a bi-monthly magazine regarding issues of compliance, risk and sustainability related to the business of Private Equity (“PE”).

This edition outlines vulnerabilities of a PE Firm’s cybersecurity framework.

Cybersecurity is a critical component in many of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals and the Australian Government’s Cybersecurity Strategy (2020), and a PE Firm has a significant role to play.

Profile of a PE Firm’s Stakeholders:

- Clients, who are usually financial institutions and professional investors, with their own clients. Examples include Australian complying superannuation funds, foreign pension funds, insurance companies, banks, family offices and other high net-worth entities, other businesses, local governments, municipal investors, etc.;

- In some cases other private fund managers, advisors or businesses, in which investments are made;

- Material service providers, including fund administrators, custodians, depositaries, banks, tax advisors, legal advisors, registered auditors, surveyors and valuers, and any other service providers;

- Regulatory bodies that have granted a financial services licence to operate a financial service business, and to offer a financial product;

- Industry and Professional Associations; and

- Committees and Advisory groups.

“A Private Equity Firm operates within a sector that demands high security and interdependence“

Identifying threats and attacks

There are two approaches recommended for identifying threats and attacks: (1) to identify and anticipate potential harm; or (2) to review the risk and potential impact of a security breach on those assets.

What critical asset is most vulnerable?

A PE Firms’ most critical asset is information. Vulnerabilities exist in the nature and movement of data, and threat actors seek out weaknesses whilst data is static, in transition, or in motion through interconnected entities.

What qualities of a PE Firm’s data that make it vulnerable to threats?

A typical PE Firm possesses at least the following data attributes making it potentially vulnerable to a cybersecurity attack:

- Static: Holds personal data in respect of any individual contacts of their stakeholders;

- Static: Holds material non-public information about its direct or indirect investments;

- Static: Holds sensitive information in connection with any of its stakeholders;

- Transition: Transfer of data between networks and systems with a mix of manual handling and automation in the collation, and capture and processing of data;

- Transition: Transfer of data through stakeholders with fragmented information systems (depending on the business life cycle), with the level of sophistication of technology dependent on buy-in from founders (Chaudhary et al. 2018);

- Motion: Data travels through a sector tainted by inconsistent utilisation of cybersecurity protection and a patchwork of differing regulatory and policy responses by national securities oversight bodies across jurisdictions (Chaudhary et al. 2018);

- Motion: Data travels through a sector comprised of “high security interdependent Firms”. The PE Firm holds information from other financial institutions or organisations, comprising of high security qualities, such as personal data, material non-public information and sensitive information.

Why is Cyber risk so harmful?

Cyber risk is harmful to a PE Firm because it is connected to many other participants who are:

- Other businesses in critical sectors of the economy;

- Other Fiduciaries of preserved wealth or significant influence (such as superannuation funds, pension funds and insurance companies); and

- Organisations that are responsible for critical national infrastructure.

“Since 2015 various OECD governments are adopting regulation”

Are there regulatory constraints?

Since 2015, to achieve best practice approaches to cybersecurity for their stakeholders, various OECD governments have adopted recommendations regarding the introduction of regulation for interconnected organisations (Gordon et al. 2015). For example:

- The United Nations (Henriksen 2019);

- The General Personal Data Protection Regime, introduced in UK and Europe in 2018 (Laube and Böhme 2016);

- The Privacy Principles on Personal Data, introduced in Australia in 2018, complemented by the Australian Government’s Cybersecurity Strategy in 2020;

- The SEC’s OCEI guidance on cybersecurity;

- The various sector specific state based legislation;

- The various standards of signatory groups, industry and professional bodies.

What are the motivational factors for cybersecurity threats?

Motivational factors of bad-faith actors based on the assets and stakeholders of PE Firms include:

- Financial gain from theft of highly confidential data. Possession of this confidential information means that threat actors are able to:

- engage in fraud to misappropriate or steal financial assets of individuals;

- possess potentially insider information; or

- release information that would cause the greatest contagion of financial loss.

- Using whistleblowing frameworks in bad faith, to exercise emotional or political beliefs. Thus, selectively releasing information that is adverse to the reputation and credibility of a PE Firm and any of its stakeholders. Typical examples include:

- Emotional: Such as former disgruntled employees, with the greatest risk arising from the departure of a senior manager. A PE Firm should monitor key senior personnel (such as any of the C-Suite, or the Founders or business line leaders), to mitigate potential harm arising from this threat (Tuttle 2014)

- Political: Not-for-profit ideologues:

- In the form of cyber espionage, who disagree on the nature, type or pace of sustainable, ethical or impact investing;

- who are motivated to cause harm or non-financial harm to businesses in whom A PE Firm invests directly or indirectly. These other businesses are targeted because of the nature of their activities are perceived to be prone to environmental, social and ethical controversies.

“Cyber terrorism propagates harm like any other crime”

Threat Actors

Threat Actors are most likely:

- Nation States undermine the integrity of another nation’s financial services sector through cyber terrorism. Cyber terrorism propagates harm in the same way as any other crime: physical or digital, economic, psychological, reputational, and social or societal. Cyberwarfare is characteristically a “persistent form of engagement” (Healey and Caudill 2020). Effective risk mitigation depends on strategic investment into effective controls and continuous alignment with international standards, and continually adapting to regulatory obligations (Gross, Canetti, and Vashdi 2017; Chepaitis 2004; Chaudhary et al. 2018).

- Hacktivists, aggrieved about the perceived lack of engagement into environmental, social or ethical activities, or perceived unethical or immoral activities undertaken by a PE Firm or by stakeholders (Cloward and Piven 2001).

- Organised criminals intending to use the personal data or materially non-public data for nefarious purposes.

Methods of Attack

Common methods of attack on a PE Firm are:

- Advanced persistent threats: This method employs a combination of the other methods (discussed below) to evade discovery, whilst gathering information surreptitiously over time. Through this coordinated and subvert approach threat actors are able to precisely target the weakest target personnel in a PE any one connected to a PE Firm (Sarabi et al. 2016; Bellovin, Landau, and Lin 2017).

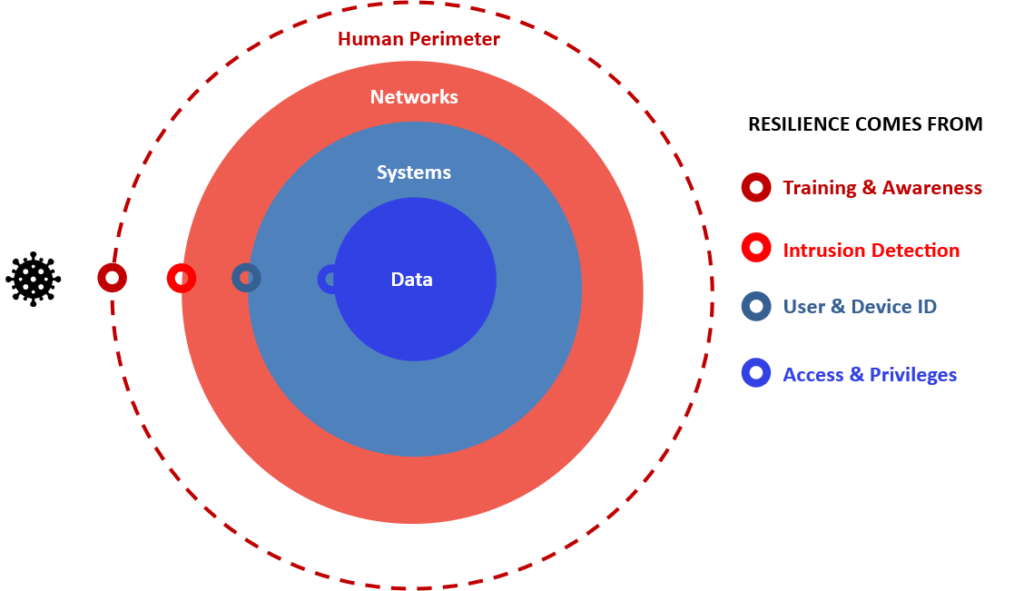

- Social Engineering: This method requires gaining trust of individuals who are the least cybersecurity proficient person in a PE Firm. Thereby, exploiting a PE Firm’s vulnerabilities by riding on weaknesses in the “human perimeter’s” awareness to cyber risk.

- Phishing: This method, like social engineering, exploits vulnerabilities through weaknesses in the human perimeter. PE Firms forget that their human perimeter also encompasses their service providers, such as third-party custodians or fund administrators. Many PE Firms still depend far too much on email as a form of communication with these providers. The sophistication and quality of these fake notices have greatly improved, making them almost indistinguishable from legitimate sources.

Phishing also succeeds by targeting overworked personnel at these service providers, who typically deal with a high volume of emails. This high stress scenario increases the likelihood of phishing emails being mistaken as legitimate. It is important to invest in penetration testing, multi-factor authentication and effective workflow design together with service providers. - Spear-phishing: This method is similar to Phishing, but is targeted specifically to certain roles (Onag 2017). Common examples are emails coming from the “CEO” going to the junior accountant in accounts payable. (Kim, Kim, and Kim 2016; Caputo et al. 2014).

- DDOS or Distributed Denial of Service: This method infects and co-opts machines in a network to inundate a target network with requests thereby blocking authentic requests.

What can you do?

We suggest you take a holistic approach to risk mitigation.

We mentor PE Firms to integrate a pragmatic and truly sustainable risk mitigation framework. This includes weaving into your policies and procedures a novel approach to law, standards and conduct we call SeCCyURE©, with training and awareness of your “human perimeter” and the integrity of data at the core of that framework.

We recommend:

- Mapping your “landscape” of networks, systems and data, and discovering threats and vulnerabilities in your landscape.

- Designinga Cybersecurity Risk Mitigation Policy and recommending protective measures.

- Designing an Incident and Emergency Response Plan.

- Designing and running a Training and Awareness Program

- Engaging a Cyber Information Security Officer services to review controls of your service providers

We will use our A4P approach©, leveraging on our experience, expertise and understanding of resilience to:

- Assess your governance. Mapping relevant (a) Law, (b) Standards, and (c) Conduct that ‘Fair, Honest and Efficient’ to your financial services business.

- Advance protective measures for your three most important capital assets: your People, your Financial position, and sensitive information you hold.

- Align your Leadership Values and Strategic Objectives to these essential categories of governance.

- Adjust the “CPI” over time by ensuring that policies & procedures:

- Communicates that all personnel and service providers have a role in compliance and cybersecurity risk management.

- Promotes commercial Risk Mitigation, adapted from required and recommended standards on Risk, and financial risk resilience.

- Identifies metrics and data that is critical, and must be readily available, whilst maintaining its integrity and confidentiality.

Who are we?

Thaddeus Martin Compliance has two Principals consultants.

Dominic Tayco:

- Is a legal practitioner, with tertiary post-graduate credentials in Cybersecurity Risk Management.

- Is currently undertaking further credentials in Sustainability Finance Public Leadership

- Has 20 years professional experience in financial services, the latter 15 years of this time spent in private equity culminating with 5 tears as the global Chief Compliance Officer of an international assets investment Firm.

- Has interests and expertise in risk scenario assessments and mitigation, data integrity and research into the innovative application of data analytics.

Darren Conlon:

- is a legal practitioner, qualified health professional, and University academic specialising in law, ethics and professional practice.

- Is currently undertaking a PhD study of confidentiality and disclosure practices in the context of risk.

- Has 15 years professional experience in the Australian health care industry, including as Insurance Officer for a listed private health care provider.

- Interests and expertise lie in professional regulation, ethical and legal issues for professions, privacy and confidentiality, and risk assessment and management.

Contact Us

Disclaimer: This is intended for discussion purposes only. Nothing in this paper should be construed as professional or legal advice.

Reference list

Bellovin, Steven M., Susan Landau, and Herbert S. Lin. 2017. ‘Limiting the undesired impact of cyber weapons: technical requirements and policy implications’, Journal of Cybersecurity, 3: 59-68.

Caputo, Deanna D., Shari Lawrence Pfleeger, Jesse D. Freeman, and M. Eric Johnson. 2014. ‘Going Spear Phishing: Exploring Embedded Training and Awareness’, IEEE Security & Privacy, 12: 28-38.

Chaudhary, Tarun, Jenna Jordan, Michael Salomone, and Phil Baxter. 2018. ‘Patchwork of confusion: the cybersecurity coordination problem’, Journal of Cybersecurity, 4.

Chepaitis, Elia. 2004. ‘THE LIMITED BUT INVALUABLE LEGACY OF THE Y2K CRISIS FOR POST 9-11 CRISIS PREVENTION, RESPONSE, AND MANAGEMENT’, JITTA : Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 6: 103-16.

Cloward, Richard, and Frances Piven. 2001. ‘Disrupting Cyberspace: A New Frontier for Labor Activism?’, New Labor Forum: 91-94.

Gordon, Lawrence A., Martin P. Loeb, William Lucyshyn, and Lei Zhou. 2015. ‘Increasing cybersecurity investments in private sector firms.(Research Article)(Report)’, Journal of Cybersecurity, 1: 3.

Gross, Michael L., Daphna Canetti, and Dana R. Vashdi. 2017. ‘Cyberterrorism: its effects on psychological well-being, public confidence and political attitudes’, Journal of Cybersecurity, 3: 49-58.

Healey, Jason, and Stuart Caudill. 2020. ‘Success of Persistent Engagement in Cyberspace’, Strategic Studies Quarterly, 14: 9-15.

Henriksen, Anders. 2019. ‘The end of the road for the UN GGE process: The future regulation of cyberspace’, Journal of Cybersecurity, 5.

Kim, Chang-Hong, Sangphil Kim, and Jong-Bae Kim. 2016. ‘A Study of Agent System Model for Response to Spear-phishing’, International Information Institute (Tokyo). Information, 19: 263-68.

Laube, Stefan, and Rainer Böhme. 2016. ‘The economics of mandatory security breach reporting to authorities’, Journal of Cybersecurity, 2: 29-41.

Onag, Gigi. 2017. ‘EY: Don’t take spear phishing for granted’, Computerworld Hong Kong.

Sarabi, Armin, Parinaz Naghizadeh, Yang Liu, and Mingyan Liu. 2016. ‘Risky business: Fine-grained data breach prediction using business profiles’, Journal of Cybersecurity, 2: 15-28.

Tuttle, Hilary. 2014. ‘Senior Managers Pose Greatest Risk’, Risk Management, 61: 52.